In countries where Jacques Kallis played at least 5 Tests, in only two - England (35.33) and Sri Lanka (35.33) - did he average less than 40 with the bat. Kallis was a great batsman, whose success wasn't limited to certain conditions; he did well almost everywhere and remained one of his team's best batsman for the majority of his career.

In countries where Jacques Kallis played at least 5 Tests, in only two - England (35.33) and Sri Lanka (35.33) - did he average less than 40 with the bat. Kallis was a great batsman, whose success wasn't limited to certain conditions; he did well almost everywhere and remained one of his team's best batsman for the majority of his career.

Kallis the bowler, however, wasn't in the same class as his batting self, something South African captains he played under were wary of. Against top 8 nations (basically oppositions most likely to test Proteas' bowling depth), Kallis, across 153 Tests, home and away, bowled just 12.5 overs per innings. He picked up 253 wickets at an average of 35.37.

Kallis' record as a bowler suggests that if he had bowled more, his numbers would've regressed further in terms of averages. At least, he didn't bowl enough for his numbers to be truly reflective of his quality.

Among Kallis' most regular teammates through his career, from Allan Donald to Dale Steyn, they all bowled more and did much better.

This isn't to say Kallis the bowler was a burden, not at all; in fact, he was a useful fifth to sixth bowling option who bowled his overs in decent support of others around him - an economy rate of only 2.84 - and served the side's balance very well.

But was he doing enough in his secondary skill to be regarded an all-rounder, let alone a great one? The numbers clearly answer, NO.

Isn't this all different to how we've always been told of Kallis? It is because therein lies the basic mistake we make while judging all-rounders.

A great all-rounder, by the most simple definition, would be one who is his team's one of the best, if not the best, cricketers in both skills.

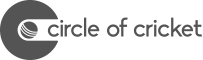

West Indies' Sir Garry Sobers is a player Kallis is widely compared with. There are debates over who among the duo is possibly the greatest all-rounder in the history of the game. Yet, like Kallis, Sobers wasn't near the bowler of his quality as a batsman. In countries where Sobers bowled in at least 5 Tests, in only one did he average less than 30. As a batsman, however, like Kallis, Sobers was great. Among countries where Sobers played at least 5 Tests, in only one did he average less than 40.

West Indies' Sir Garry Sobers is a player Kallis is widely compared with. There are debates over who among the duo is possibly the greatest all-rounder in the history of the game. Yet, like Kallis, Sobers wasn't near the bowler of his quality as a batsman. In countries where Sobers bowled in at least 5 Tests, in only one did he average less than 30. As a batsman, however, like Kallis, Sobers was great. Among countries where Sobers played at least 5 Tests, in only one did he average less than 40.

Among West Indies batsmen Sobers played with (min 40 innings), he outbatted all of them, across 93 Tests, but among bowlers Sobers played with (min 30 innings), he was comfortably outbowled by the likes of Lance Gibbs, Charlie Griffith, Wes Hall and did better than only one other.

So why are people not acknowledging Sobers specifically as a great batsman instead of raving over him as an all-rounder, especially when there is an obvious gap in the record of his primary skill to that of the secondary one?

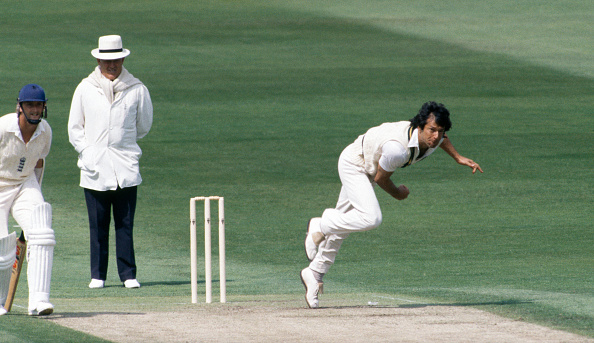

Imran Khan is still considered the best-ever Pakistan captain. Not just for winning the 1992 World Cup or for leading a rare visiting side that competed with the mighty West Indies during the 80s. But also for keeping such a temperamental team together in thick and thins, backing youngsters like Wasim Akram, who retired from the game inarguably one of the best-ever fast bowlers. Imran left an amazing legacy behind as captain.

However, we shall also not forget what an excellent cricketer he was. Imran picked up 362 wickets and scored 3,807 runs at averages of 22.81 and 37.69, respectively.

Imran the bowler, his primary skill, was plagued by a career-threatening injury when he was at his peak. Yet, in countries where Imran played, in not a single one did his average touch 30. As a batsman, Imran did well everywhere, except West Indies and Sri Lanka, where he made up for the lack of runs with his bowling.

A comparative study with his teammates reveals that Imran as a batsman, although a valuable contributor, wasn't the best of his side but easily its most outstanding bowler - which is how he shall best be remembered.

But Imran was seen as part of a club of four all-rounders from the late 70s till the end of the 80s. Even if such a club really existed, he was the most exceptional of the lot. In fact, a study in numbers quite tellingly reveals that the likes of Ian Botham, Kapil Dev and Richard Hadlee didn't have anywhere near as strong a claim of being deemed great Test all-rounders as Imran.

Hadlee was an outstanding seam bowler, which his record - average below 30 in all but one country where he played - perfectly reflects. But he wasn't a batsman of the same class, averaging only 27.16 across 86 Tests for New Zealand.

Kapil, the 1983 World Cup-winning captain, would be the first to admit that his numbers in Tests left a lot to be desired, across different conditions and in both skills.

Botham comes across as the closest thing to Imran, but Beefy's numbers, both home and away, against the best team of those times - the West Indies - don't give a good reading.

This isn't at all an exercise of putting cricketers down from the pedestal they've been put on, but we need to know more about them than what we've always been told. And while studying that, we shall also understand the basic mistake we've made in assessing their all-round pedigree.

In all fairness, still, people like Kallis, Sobers, Imran, Botham, Hadlee and Kapil were offering bonus level secondary skill to their teams because they were exceptional at their main skill, which they were first picked for.

Teams are constantly hoping to find such gems, and often make basic errors in that search. They look for all-rounders and end-up selecting bits & pieces cricketers, players who aren't exceptional in any one of the two skills, but operate at just about a reasonable level. Such players are regularly exposed in international cricket and are detrimental to a side's overall balance.

In some cases, teams' search for all-rounders does great injustice to the skill a player is more likely to succeed in. Ben Stokes is one such cricketer.

In some cases, teams' search for all-rounders does great injustice to the skill a player is more likely to succeed in. Ben Stokes is one such cricketer.

Stokes averages 36.54 with the bat and 32.68 with the ball in his Test career so far, which unfortunately leaves him vulnerable of being categorised in that 'bits & pieces' column.

Yet, throughout his career, Stokes has shown the ability to play some outstanding knocks. He is more impactful with the bat than he is with the ball, which the upsurge in his batting average in wins (42.44) perfectly reflects.

So one wonders, wouldn't England be better served with Stokes focussing solely on his batting and not being looked at as an all-rounder, who is having to compromise on his primary skill, just because he could bowl a bit.

In ODIs, at least, England has given Stokes his due. He often bats in the top five (avg 40.64, SR 93.64) but bowls (approx) 6.06 overs per innings (economy 6.02, avg 41.71) only. When needed the most, Stokes was there keeping England's World Cup final hopes alive. He is more likely to score 16 runs required to win a super-over than he is to defend that many runs with the ball.

Hardik Pandya is another cricketer in the same mould, the ones 'who make things happen'. Hardik was first picked in 2016 as India's search for an all-rounder found its latest fit. But he was better than others trialled for the spot. Hardik could hit the ball big and bowl above 140 kmph, good raw materials to work with, especially in the 50-over version.

Hardik Pandya is another cricketer in the same mould, the ones 'who make things happen'. Hardik was first picked in 2016 as India's search for an all-rounder found its latest fit. But he was better than others trialled for the spot. Hardik could hit the ball big and bowl above 140 kmph, good raw materials to work with, especially in the 50-over version.

ODIs, with the limit on each bowler upto 10 overs and still requiring good-enough batting depth till at least No.7, are designed for such cricketers to flourish. Fielding teams find making up the fifth bowlers' quota much easier in ODIs than they do in T20 cricket, employing defensive field settings during the middle phase of the innings, where batting sides also play the waiting game. In that process, wickets are considered bonus, with all the focus on maintaining a reasonable economy rate.

Hardik has gone at an economy rate of 5.53 versus top 8 nations in his career so far, averaging 41.83 (7.08 overs per innings), with 49 wickets.

As a batsman, Hardik's importance to that inconsistent middle-order clearly stands-out. He is an ever-improving power-hitter, with a strike-rate of 116.27 for 950 runs across 36 innings versus top 8 teams.

However, in whatever rare opportunities Hardik has got slightly up the order, he has shown the range to his batting, the ability to play around the field and rotate the strike regularly, like proper batsmen do.

It can be said with confidence that if India relieves Hardik of some of his bowling burden, he would be able to flourish even more with the bat.

India could've done this in that phase between October 2016 till January 2019, when Kedar Jadhav did well as a fill-up bowler with those innocuous-looking, side-arm off-spinners, going at an economy rate of 5.18 versus top 8 nations despite bowling almost 5 overs per innings.

Yet, in the games Hardik played alongside Kedar in that period, his workload as a bowler decreased only marginally, from 7.08 to 7.00 overs per innings. But Hardik's batting average improved during that phase (35.17), without compromising much on his strike-rate (116.11).